05 Sep 1977 Mini Transat Founder Bob Salmon’s Race Dream

1977 Mini Transat Race Details

- Start: South coast of England.

- Destination: Antigua, West Indies.

- Route: The race was in two stages, with a stopover in the Canary Islands.

- Purpose: To create a more accessible and human-powered ocean race for smaller boats.

Key Characteristics

- Solo Sailors: The race is single-handed, requiring a single person to navigate and sail the boat.

- Small Boats: Participants sail Mini 6.50 yachts, which are about 21 feet long.

- No External Assistance: Sailors are entirely on their own for much of the race, with no external aid.

Significance

The 1977 Mini Transat marked the beginning of a legendary and challenging event in ocean sailing.

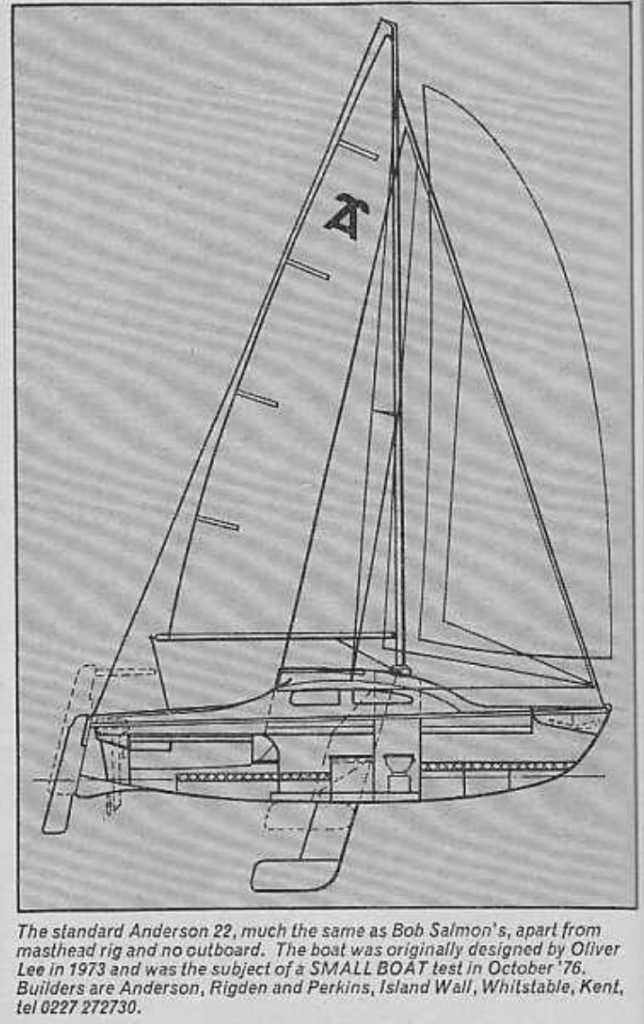

A standard Anderson 22, with its masthead rig and sail plan visible. The diagram shows the boat’s keel and rudder configuration, which is the same model Bob Salmon used in the race. It was originally designed by Oliver Lee in 1973.

The 1977 Mini Transat marked the beginning of a legendary and challenging event in ocean sailing. It has grown from its modest beginnings to become a crucial platform for launching the careers of many professional sailors, including Michel Desjoyeaux and Ellen MacArthur.

- Boat: Salmon’s boat was a modified Anderson 22. The original Anderson 22 was designed by Oliver Lee in 1973.

- Performance: A report indicates that Salmon completed the race’s first leg to Tenerife in 10th position and continued on to finish 15th overall.

- Context: The Mini Transat was founded by Bob Salmon to be an accessible offshore race for small, production-based yachts. Its first edition featured 38 competitors and started from Penzance, England.

The Results

| 1977 Mini Transat Results | |||

| Rank | Boat Name and Number | Skipper | Completion Time |

| 1 | PETIT DAUPHIN (64) | Daniel GILARD | 22 Days 18h 10′ |

| 2 | SPANIELEK (77054) | Kasimierz JAWORSKI | 23 Days 05h 45′ |

| 3 | REVE DE MER TRONQUE (35) | Halvard MABIRE | 23 Days 19h 05′ |

| 4 | MUSCADET (351) | Jean-Luc VAN DEN HEEDE | 23 Days 22h 48′ |

| 5 | CHALLENGER (37) | Antoine DI MEGLIO | 24 Days 13h 07′ |

| 6 | GET (451) | Philippe MUSEUX | 25 Days 19h |

| 7 | MISTENFLUTE (105) | Rémy MARSAULT | 25 Days 23h 28′ |

| 8 | PROTO – LILIPUT (110) | Claude MARSAULT | 26 Days 12h |

| 9 | NAM (122) | Albert CHALTIN | 26 Days 16h 15′ |

| 11 | MUSCADET (79) | Franck GENIN | 28 Days 00h 49′ |

| 12 | EDELWEISS (65) | Bruno PEYRON | 28 Days 21h |

| 13 | KINGFISHER (95) | David WOOD-STOKYN | 29 Days 11h |

| 14 | AROUVAN III (104) | Luc FREJAQUES | 29 Days 19h 10′ |

| 15 | ANDERSON (71) | Bob SALMON | 32 Days 00h 47′ |

| 16 | SEA ROSE (119) | Michel DEVILLIERS | 34 Days 21h 12′ |

Last autumn saw the first transatlantic race for singlehanded yachts under 6.5 metres. Bob Salmon not only organised it, but also took part as a competitor in the first British yacht to finish.

In one branch of our sport, the ability to raise huge sums of money from sponsorship has become as essential as the ability to sail. I refer of course to singlehanded ocean racing. Since the 1964 transatlantic race, sponsorship has been a prime factor behind each winner, and the vast majority of entrants have started without any real chance of victory.

I am not opposed to sponsorship, indeed I have tried to obtain it myself on occasions, but I would ask that if the majority of entrants start a race without any chance of winning, is it really a race? It is not possible, or even necessarily desirable, to prevent sponsorship. To be realistic, the man whose wife goes to work to keep the home intact while he is away racing is just as sponsored as another with factory or even government backing. The only difference is that the first has a happy home to come back to, the second may well win the race.

What one can do though, is to limit the effects of sponsorship, and two years ago I thought up the idea of a trans-ocean race which would be restricted to very small yachts. Six and a half metres was the length decided on as adequate for an ocean crossing, but so small that cost would not be prohibitive. Anyone who wanted to race would have an entry at about the maximum size, and therefore they would start with a genuine chance of winning. You think I set the overall length too short? Refer back to your history books! Boats of this size or less have crossed all the world’s oceans, often with two or more crew on board. In modern times we seem to forget much of the ability and seamanship of our forefathers.

—

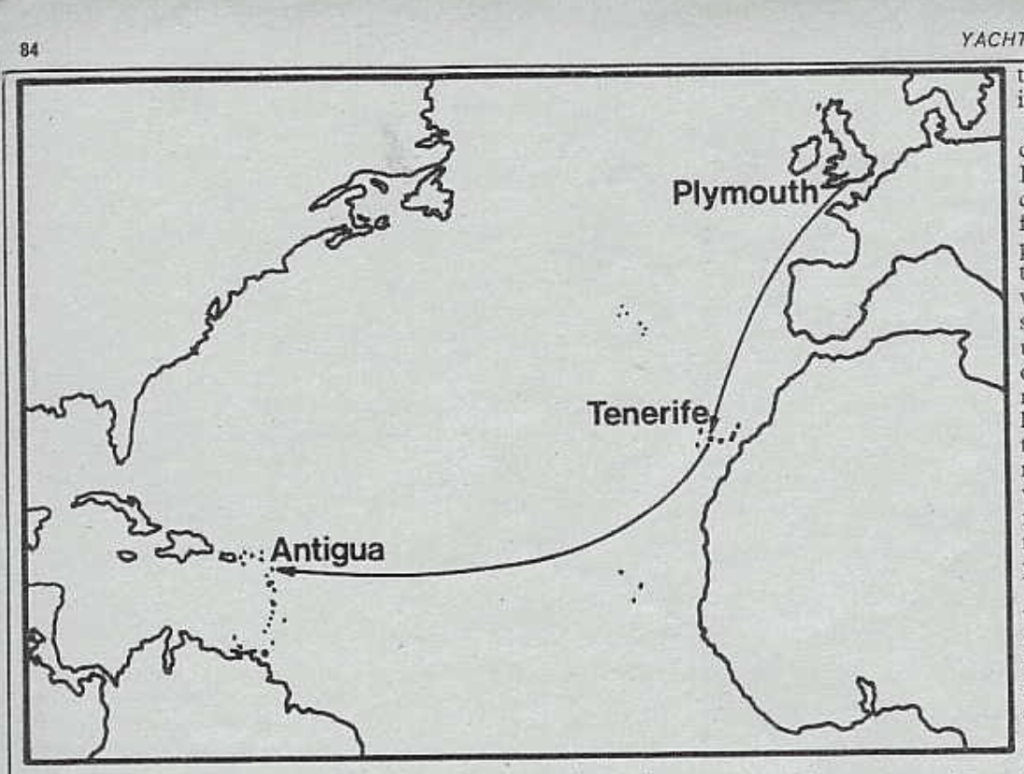

The Route of the 1977 Mini Transat

A map showing the route of the 1977 Mini-Transat race. The map traces a path from Plymouth, England, to Tenerife, and then across the Atlantic Ocean to Antigua.

In keeping with the small size of craft, I chose the traditional Trade Winds route to the West Indies. We would leave from Penzance, sail across the Western Approaches, the Bay of Biscay, past Spain and Portugal to Tenerife in the Canary Isles, and then after a rest and a second start, we would race across to Nelson’s Dockyard in beautiful English Harbour, Antigua. This way the entrants would be sailing into progressively warmer water, and could hope for a high percentage of favourable winds and currents. The only problem about this route is timing. In order to miss the hurricane season it is wise to arrive in the West Indies after the middle of November, and this means a late Autumn start from the UK with the risk of bad weather right in the early stages. To minimize this risk I decided to make the first leg from Penzance to Tenerife compulsory but non-competitive. Entrants would thus not have the pressure of racing, and would be able to heave to or even seek shelter along the route without penalty.

—

Early entries

I did not expect very much interest in a first race of this kind, but after writing some ‘reader’s letters’ to a couple of yachting magazines, I announced that my wife Beryl and I would organize a race along the lines set out in the Autumn of 1977. We received over 300 enquiries from 29 different countries! Due to space limitations in Penzance harbour we were quite unable to cope with all this interest, and were forced to bring the closing date for entries forward by three months. Sadly, we had to reject a number of entries although as events turned out there would have been room in the harbour thanks to the non-arrival of an expected fleet of East Coast trawlers.

I had every intention of taking part in the race myself, so apart from running my own yacht delivery business (I specialize in long distance work and this means long periods away from home), I was also trying to build a prototype yacht for the race, an almost flat bottomed downhill racer. In our spare time Beryl and I were organising the race, and this was to take far more time than I had imagined. The net result of course was that progress on my own boat was very much slower than hoped for. Just at the time when we began to have doubts about whether my own entry would be ready in time, Nick Wright, the Sales Manager for Anderson, Rigden & Perkins of Whitstable telephoned me. Nick had been one of the first to enter our race, and I knew he was having a slightly modified Anderson 22 built. Now he was to tell me that pressure of work was forcing him to withdraw from the race, but his boat was almost ready and would I like to use her? It sounded the perfect answer.

Anderson Affair looked very smart, with race numbers already painted on her red hull, and I just made a few suggestions to Nick about the location for the safety harness jack stays and other details of personal preference. The only real problem concerned the mounting of the Gibb/Haslar trim-tab self steering gear. This was a new model, and as mounted, severely restricted the normal swing of the rudder. This was due for inspection by the makers and I was assured that any problems would be sorted out in early sea trials. Unfortunately marine trade delivery dates tend to be on the optimistic side, and Anderson Affair was no exception. We only managed to get her launched a few days before the start, and discovered several problems, the worst being a self steering gear which wouldn’t, and a badly flexing upper mast section. The mast problem came about because the race boat was masthead rig rather than the standard 7/8ths, and also had a different standing rigging set up. Slightly wider spreaders and the addition of upper diamonds cured the problem, but only at the expense of precious time in the days leading up to the start.

—

Steering trouble

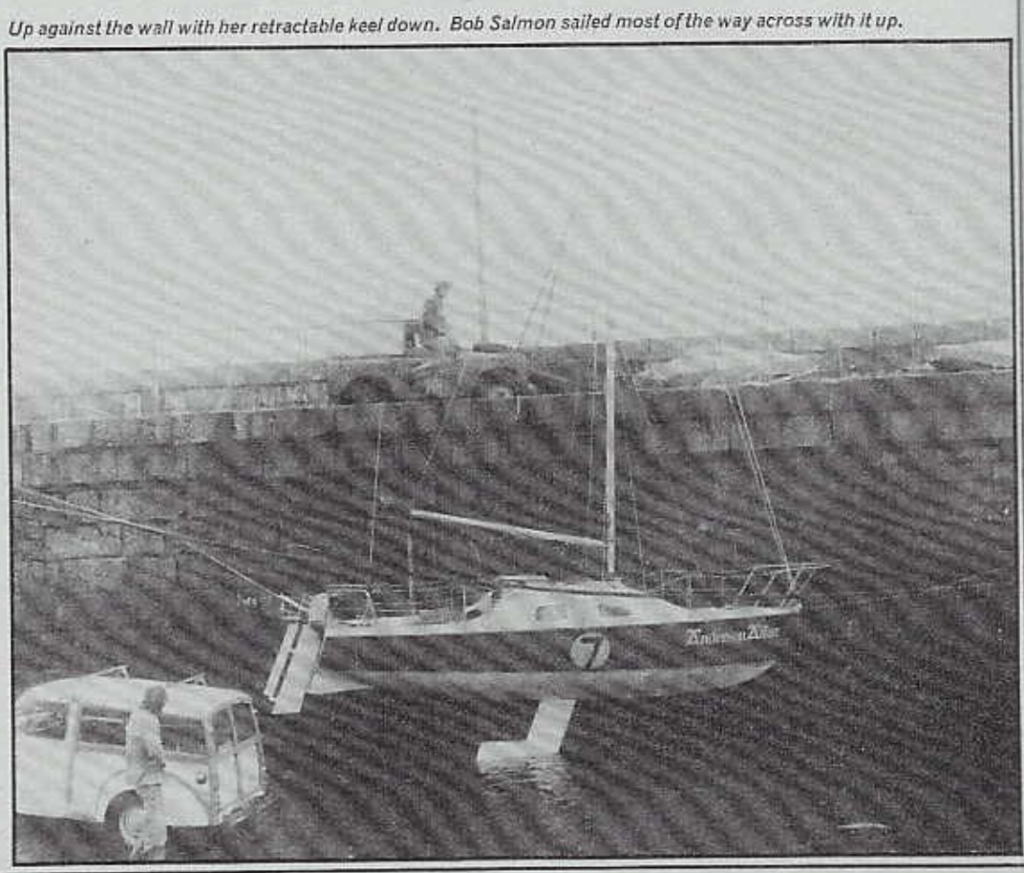

The Anderson Affair, suspended over the water. The boat is shown with its retractable keel in the down position, with a caption noting that the author, Bob Salmon, “sailed most of the way across with it up.

Despite remounting the Haslar gear and trying various suggestions from the makers to vary the feedback ratio, it didn’t improve. Possibly it was totally unsuited to the Anderson’s keel/rudder configuration-certainly I never managed to get it working efficiently. There was a hectic week in Penzance harbour as twenty six entrants from eight different countries had their boats inspected by a team of scrutineers from Penzance Sailing Club. The general standard of preparation was very high and only one boat was rejected, but there were the usual last minute panics as entrants got the local sailmaker to run up Antiguan courtesy flags, etc.

I crossed the line with the other entrants, but then put back into Penzance for three hours to finish stowing all the ship’s gear and get the trim about right. Such had been the pace of preparation, that we had only finished antifouling at two that morning, and had mounted an acrylic astrodome on the main hatch just half an hour before the start. The winds were very light as I left, and there were still a couple of sails in sight so I felt the time lost had been well spent. Within eighteen hours we were down to storm jib and triple reefed main in the first of three gales over the next ten days. The third gale was the tail end of storm force ten, but after that the weather improved and Anderson Affair ran South under twin genoas averaging 115 miles a day for the last six days before sailing into the modern fishing harbour of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. The passage had taken three weeks and we were the first English boat to arrive, in tenth position overall.

—

Second leg

The sunshine of Tenerife made for a relaxing fortnight as we waited for the other entrants to arrive. I found that the gales at the beginning of the race had scattered the fleet. Some had returned to the UK, and despite attempts to rejoin the race had been forced to withdraw. Others had run to ports in Spain and Portugal for shelter, and were now struggling in very light winds. The second leg of the race was a disappointment for me. With some experience of the Anderson I knew she would perform best in fresh to strong winds, and I headed South to find the Trade Winds as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, the Trades were light and a long way South last winter, and in the first eight days of the trip I only made 200 miles in the right direction.

After that a fast passage was impossible. Once we found wind, Anderson Affair provided some exciting sailing. Even with the modified masthead rig I felt she could have done with more sail area, but with the full main and twin boomed out genoas she regularly surfed over nine knots, with excellent downwind control. The big problem was the lack of efficient self steering. I had to steer by hand all day, and then reduce sail drastically at night, just to keep her pointing in approximately the right direction. Even so, we managed a best day’s run of 126 miles, and regularly topped 120 miles in a day. After twenty-nine days we were within 40 miles of Antigua when a rudder fitting failed and the rudder came adrift. We lost some hours in re-hanging it on temporary fastenings, and then closed the island during darkness. English Harbour has no lights or radio beacons, so rather than attempt to enter it during the moonless night we just ghosted along under mainsail and passed the entrance while waiting for daylight. On passing the harbour entrance, one of the temporary fastenings failed and the rudder jammed hard over. I had the CQR all ready in the cockpit, and quickly threw it over but the nylon warp parted on a coral head and we were driven up onto Cade Reef.

The rest of the night passed in a crashing and pounding on the reef which I shall never forget. As each new wave came in we were picked up and dropped again, a little higher up the reef, and it seemed certain that the hull would just break up. At daylight some local skin divers came out and helped me to off load some of the heavier gear into my dinghy and get it ashore. They rather gleefully told me that we were the fourth yacht to go onto Cade Reef within the year, and that all the others had been lost.

—

End of an affair?

It proved impossible to get a towline across to our hired power boat, and we were only able to get my personal effects off and wait for what seemed the inevitable end, but after eighteen hours Anderson Affair managed to jettison her keel in a hole between coral heads, and floated across the reef, still with her rig standing and to all appearances undamaged. We towed her into Falmouth Harbour for the night, and then the following morning back to the entrance to English Harbour where I sculled her across the line to be the first British arrival. Since I had received assistance in getting off the reef I did not claim a finishing position, but I know we made it and was very proud of the little red Anderson.

—

Combat diet

Packs Food for the trip was not too much of a problem. I stocked up with dehydrated basic foods such as beef and chicken currys, vegetables and soups, wholesale from SWEL. I was also lucky in discovering a supply of ex-army one man American combat food packs in Moto Sails of Weymouth. These packs are boxed in twelves and were selling for £7.50 a box. Since each is different and the variety includes steak, turkey etc, as well as daily biscuit and jam or peanut butter and other goodies, they make an interesting change to the daily diet. In addition of course, I carried fresh eggs, vegetables etc as long as they lasted.

HM Customs are always generous towards small boat sailors, and we were allowed to draw bonded stores for the journey. I took two cases of spirits but hasten to point out that the race was spread out over three months, and much of the booze was for on board hospitality in Tenerife and Antigua.

Loss of time is probably the most expensive item. The race plus preparation must have taken at least four months of last year, and even though I flew back from Antigua, it was still a month later before I had cleared everything up and was available to work again. My loss of earnings for the whole period must be £2,000 or more.

—

The next Mini Transat race

Was it all worthwhile? Most of the entrants thought so, and have already asked us to organise a second race in the Autumn of next year. We are now looking at various suggestions as to how this could best be done. For my own point, I enjoyed the race, although I would never again try to organise and take part in an event at the same time.

—

What of Anderson Affair?

This successful crossing was a testament to the new style of racing pioneered by the 1977 Mini Transat.

We took an almost standard British cruising yacht and with the minimum of preparation sailed her very hard for 4,500 miles. We didn’t win but to be honest, we never thought we could. Had we not been plagued with self steering problems the crossing would have been quite a bit faster, but even so, thirty days is still a good transatlantic crossing. The only item to fail was the rudder hanging, and it was a great pity that this should have had the effect it did. The defect has now been modified on the production boats being built, so there has been a useful spin-off from the race to the production line, which is as it should be.

For anyone considering the challenge of an Ocean crossing I would suggest that the cost does not have to be too formidable. It would be possible, even at today’s prices, to buy a secondhand craft and with a few simple modifications sail her to the West Indies for under £2,000. Another £100 or so for food to make the return journey and you could have the adventure of a lifetime, spread over eight or nine months, and still have a boat which inflation might well have revalued to cover the whole trip. A free trip, almost. All you need is the time!

If you want to go racing then the story will be a little more expensive, but it should be possible to, say, build a modified Intro or something similar, and enter with a genuine chance of victory for £5,000 or so. At the end of the race you should still have a valuable race machine.

Dreams are what we make of them. Many dream of the flying fish route to the sunshine, but it is possible to make those dreams come true sometimes. Just put your estimates down on paper, double them, and then go anyway. See you out in Antigua….

—

In summary

Cost of the Mini Transat: 1977 vs. Today

Cost in 1977

According to the documents you provided, the total cost for Bob Salmon’s participation in the 1977 Mini Transat was approximately £5,635. This total includes:

- Boat and Modifications: £4,508

- Personal and Race Expenses: £1,127

The article also notes that the average price of boats entered in the race was between £7,000 and £10,000, with some prototypes costing up to £15,000.

1977 Costs Adjusted for Inflation

Based on UK inflation data from 1977 to 2025, a pound today has approximately 7.94 times the buying power of a pound in 1977.

- Bob Salmon’s Total Cost (inflation-adjusted): The £5,635 spent in 1977 would be roughly £44,736.90 today.

- Average Boat Cost (inflation-adjusted): The average boat price of £7,000 to £10,000 would be equivalent to £55,580 to £79,400 today.

Cost Today

Current costs for the Mini Transat are significantly higher than the inflation-adjusted 1977 prices, primarily due to advances in technology and the competitive nature of the race.

- Race Entry Fees: Recent entry fees have been reported to be around €8,500 ($3,200 for a 2023 race).

- Yacht Cost: While older boats can be found for less, a race-winning Mini 6.50 yacht today can cost upwards of €300,000.

**Credit:** This article originally appeared in Yacht and Boat Owner, May 1978.